[ad_1]

E. coli grows in our guts, sometimes with the unfortunate effect, and DNA facilitates scientific advances like biofuels and Pfizer’s covid vaccine. Now this multi-talented bacterium has a new trick: It can solve a classic computational maze problem using distributed computation – allocating the necessary computations among different genetically engineered cell types.

This outstanding achievement is a credit to synthetic biology, which aims to equip biological circuits like electronic circuits and program cells as easily as computers.

labyrinth experimentIt’s part of what some researchers see as a promising direction in this field: instead of designing a single cell type to do all the work, they design multiple types of cells to do the job, each with different functions. Working together, these engineered microbes can “calculate” and solve problems like multicellular networks in the wild.

Until now, taking full advantage of biology’s design power, for better or worse, has eluded and frustrated synthetic biologists. “nature can do this (think of a brain), but we “I don’t know yet how to design at this overwhelming level of complexity using biology,” says Pamela Silver, a synthetic biologist at Harvard.

working with E. coli As maze solvers, led by biophysicist Sangram Bagh at the Field Institute of Nuclear Physics in Kolkata, it is a simple and fun toy problem. But it also serves as a proof of principle for distributed computing across cells and shows how more complex and practical computational problems can be solved in a similar way. If this approach works at larger scales, it could unlock applications for everything from medicine to agriculture to space travel.

“Delivering the load in this way will build significant capacity as engineering moves towards solving more complex problems with biological systems,” says David McMillen, a bioengineer at the University of Toronto.

How to make a bacteria maze

Acquisition E. coli Solving the maze problem required some ingenuity. The bacteria did not wander through a palace maze of well-pruned hedges. Instead, the bacteria analyzed various maze configurations. Setup: a maze for each test tube, each maze produced by a different chemical mixture.

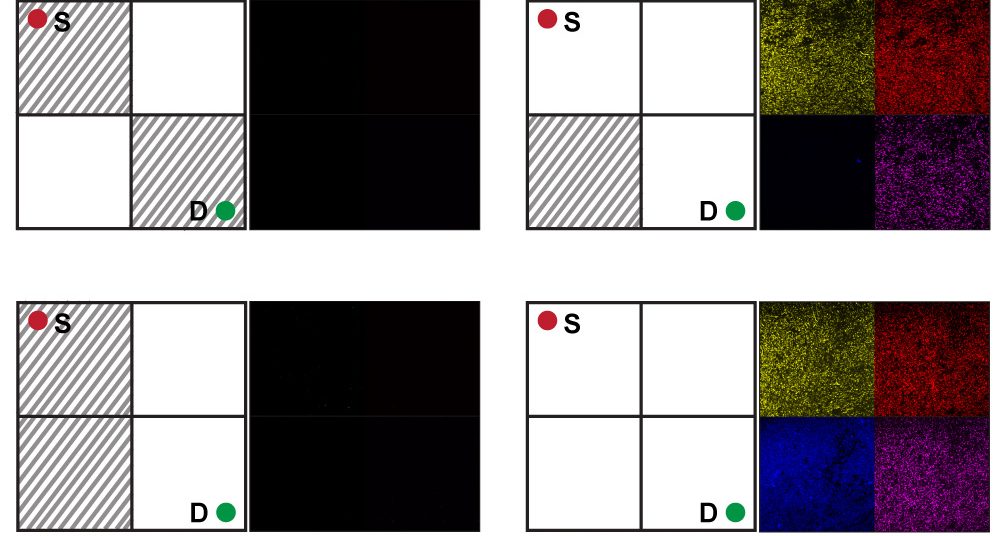

The chemical prescriptions were taken from a 2×2 grid representing the maze problem. The upper left square of the grid is the start of the maze, and the lower right square is the destination. Each square in the grid can be an open path or a block, giving 16 possible mazes.

Bagh and colleagues mathematically translated this problem into a truth table consisting of: oneAnnual 0s indicates all possible maze configurations. They then matched these configurations to 16 different mixtures of the four chemicals. The presence or absence of each chemical corresponds to whether a particular square in the maze is open or blocked.

The team designed multiple sets E. coli with different genetic circuits that detect and analyze these chemicals. Together, the mixed population of bacteria functions as a distributed computer; each of the various cell clusters performs part of the computation by processing the chemical information and solving the maze.

The researchers conducting the experiment first E. coli In 16 test tubes, he added a different chemical maze to each and let the bacteria grow. after 48 hours, if E. coli failed to detect a clear path through the maze – that is, if the necessary chemicals were not present – the system remained dark. If the correct chemical combination is present, the corresponding circuits “turn on” and the bacteria collectively express fluorescent proteins in yellow, red, blue, or pink to indicate solutions. “If there is a way, a solution, the bacteria shines,” Bagh says.

KATHAKALI SARKAR AND SANGRAM BAG

What Bagh finds particularly exciting is when he shuffled through all 16 mazes, E. coli provided physical evidence that only three were solvable. “It’s not easy to calculate this with a mathematical equation,” says Bagh. “With this experiment, you can visualize it very simply.”

lofty goals

Bagh envisions such a biological computer that aids cryptography or steganography (the art and science of hiding information) using labyrinths. encrypt and hide data respectively. But the results extend beyond these applications to the higher ambitions of synthetic biology.

idea of synthetic biology It dates back to the 1960s, but the field began in 2000 when synthetic biological circuits (specifically, a toggle switch and one oscillator) this made it increasingly possible to program cells to produce desired compounds or to react intelligently in their own environment.

[ad_2]

Source link