[ad_1]

One of those users for decades was Thomas Hofeller, “Michelangelo of modern gerrymander” is the longtime Republican National Committee’s official re-regional director, who died in 2018.

Gerrymandering schemes, “cracking” and “bundling” – to distribute votes to a party across counties, thus diluting their power and cramming like-minded voters into one district, wasting the power they would have elsewhere. The city of Austin, Texas is divided into six districts (it is the largest US city not anchored in a district).

In 2010, the full force of the threat came from the Majority Republicans Rezoning Project, or REDMAP. It spent $30 million in state legislatures, with winning results in Florida, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Michigan and Ohio. “The wins in 2010 gave them the power to chart in 2011,” says the book’s author, David Daley. Ratf**ked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy.

“What used to be a dark art is now a dark science.”

MICHAEL LI

The advancement of technology by leaps and bounds since the previous redistribution cycle has only strengthened the result. “It made gerrymanders withdrawn that year much more enduring and enduring than any other gerrymanders in our nation’s history,” he says. “It is the complexity of the computer software, the speed of the computers, the amount of data available, that makes it possible for partisan cartographers to run their maps through 60 or 70 different iterations and really improve and optimize the partisan performance of those maps. ”

As Michael Li, a rezoning expert at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University’s law school, says: “What used to be a dark art is now a dark science.” And when manipulated maps are applied in an election, he says, almost impossible to overcome.

A mathematical microscope

Mattingly and his duke team They stay up late writing code that they hope will produce a “big payoff algorithmically” – preparing for a real-life implementation of their latest tool, which was released in an article with a technically stunning title (currently under review).Multiscale Coupling-Split Markov Chain Monte Carlo for Rezoning”

However, advancing technical discourse is not the top priority. Mattingly and his colleagues hope to educate lawyers, judges, mathematicians, scientists – anyone interested in the cause of democracy – as well as politicians and the public. In July, Mattingly gave a public lecture with the easier-to-understand headline: “Can you hear the will of the voters?”

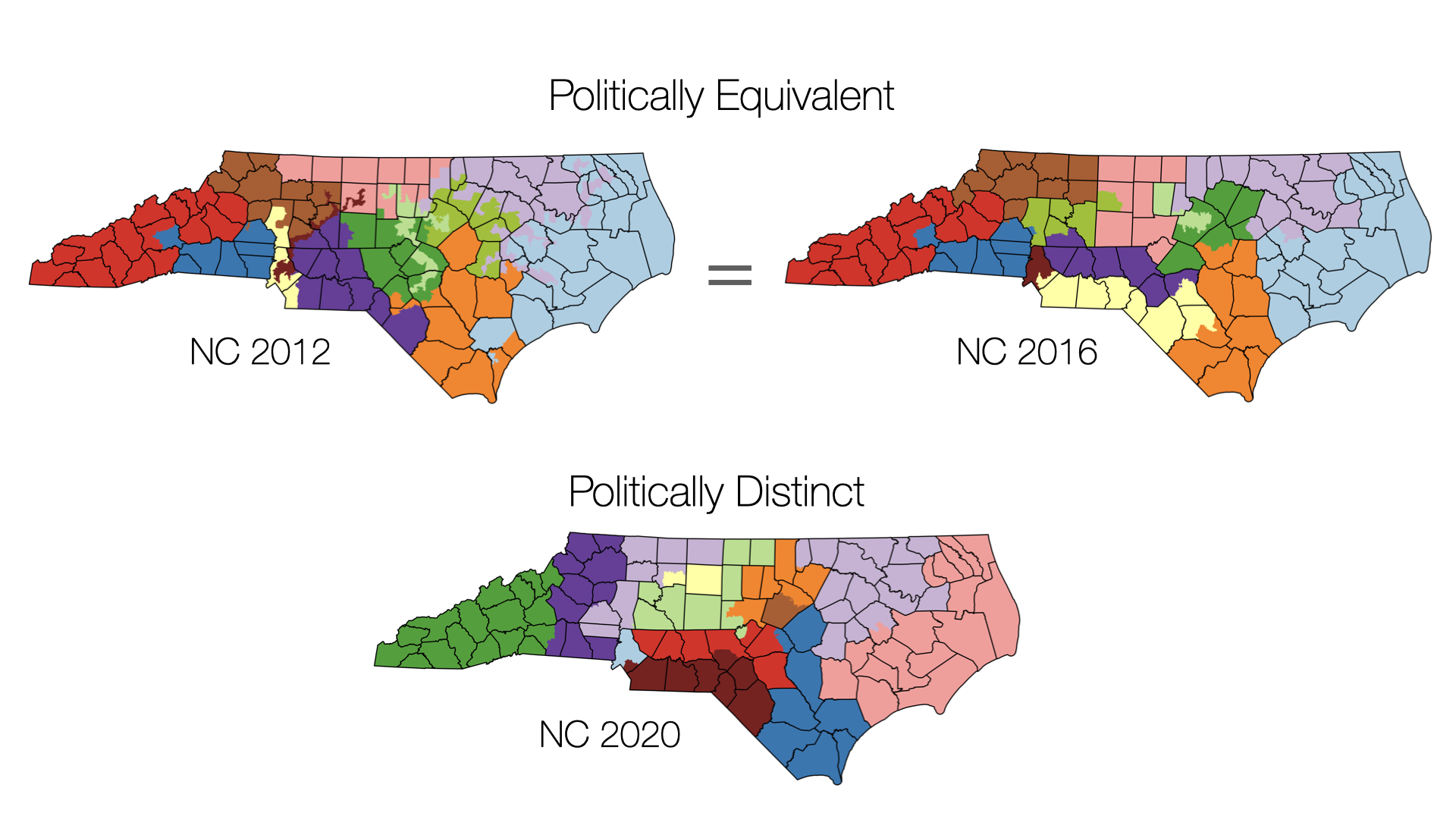

The misshapen areas are often thought to be a sign of a gerrymander. With the 2012 map of North Carolina, congressional districts are “very weird-looking monsters,” says Mattingly, who (along with key collaborator Greg Herschlag) provided expert testimony in some of the lawsuits that followed. Over the past decade, there have been legal challenges across the country – in Illinois, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin.

But while such amorphous neighborhoods “make really nice posters, coffee cups and t-shirts,” says Mattingly, “the truth is, stopping the weird geometries isn’t going to stop the gerrymandering.” And indeed, with all the technologically advanced sleight of hand, a gerrymandered map can be hard to spot.

jonathan mattingly

Tools developed simultaneously by several mathematicians provide what is called “extreme outlier testing.” Each researcher’s approach is slightly different, but the bottom line is that a map suspected to be Gerrymander is compared to a large collection or “collection” of neutral, unbiased maps. The mathematical method at work – what is it called? Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithms— generates a random map sample from a universe of possible maps and reflects the probability that any map drawn will meet various policy considerations.

Community maps are coded to capture the various principles used to plot regions and take into account the way these principles interact with a state’s geopolitical geometry. Principles (which vary from state to state) include criteria such as keeping counties relatively compact and connected, making them roughly equal in population, and protecting counties, municipalities, and communities of common interest. And district maps must comply with the U.S. Constitution and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

With the Census Bureau’s release of 2020 data, Mattingly and his team will load the dataset, run their algorithms, and create a collection of typical, neutral zone plans for North Carolina. From this wide distribution of maps and taking into account historical voting patterns, they will discern criteria that should serve as scarecrows. For example, they will evaluate the relative probability that these maps will produce a variety of election outcomes—say, the number of seats won by Democrats and Republicans—and by what margin: a 50-50 split in the vote and a reasonable vote. A neutral map is unlikely to give the Republicans 10 seats and the Democrats just three seats (as in the 2012 map).

“We use computational math to figure out what we can expect as results for neutral maps, and then we can compare it to a particular map,” says Mattingly.

They’ll announce their findings by mid-September, and then hope state legislators will heed the scarecrow. When new maps of the region are proposed later in the fall, they will analyze the results and engage in the resulting public and political debates – and if the maps are suspected of being gerrymandered again, there will be more lawsuits by mathematicians to file again. play a central role.

“I don’t want to convince someone that something is wrong,” Mattingly says. “I want to give them a microscope so they can look at a map and understand its features and then draw their own conclusions.”

PERMISSION PHOTO

When Mattingly testified by analyzing two subsequent iterations of North Carolina’s district maps in 2017 and 2019, the court agreed that the maps in question were overly partisan gerrymanders who discriminated against Democrats. Wes Pegden, a mathematician at Carnegie Mellon University, testified in the Pennsylvania case using a similar method; The court agreed that the map in question discriminated against Republicans.

“Courts have long struggled over how to measure partisan gerrymandering,” Li says. “But then when the courts downloaded the maps using some of these new tools, it seemed like a breakthrough happened.”

When the North Carolina case reached the US Supreme Court (along with a Maryland case) in 2019, mathematician and geneticist Eric Lander, a professor at Harvard and MIT and now President Biden’s top science adviser, observed briefly: computer technology has caught on to the problem it poses.” The extreme-outlier standard – a test that simply asks “Which part of the rezoning plans is less extreme than the proposed plan?” – “considered a direct, quantitative mathematical question. Right Reply.”

majority of judges turned out to be the opposite.

“The only judges who have trouble seeing how math and models work are the five judges in the Supreme Court,” Li says. “State and other federal courts have managed to implement this—it wasn’t beyond the courts’ intellectual ability to handle, like a complex gender discrimination case or a complex securities fraud case. But the five judges of the Supreme Court said, ‘This is very difficult for us.’”

“Also, ‘This is not for our fix – it’s states’ fix; This For Congress to fix; It’s not our job to fix it,” says Li.

Will it make a difference?

As Daley sees it, the Supreme Court ruling gives state lawmakers “no green light and no speed limit on partisan gerrymanders they can take out when mapping later this month.” At the same time, he says, “Technology has evolved so much that it’s now a place we can use it.” [it] to see tech-driven gerrymanders created by lawmakers. ”

[ad_2]

Source link